>

WITHIN HOURS OF THE assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as president of the US. He rode an outpouring of national sympathy and support that, a year later, resulted in a landslide victory in which he took more than 60% of the vote against Sen. Barry Goldwater. When I heard references to him as Landslide Lyndon, it made perfect sense. It was not until I read Robert Caro’s biography of Johnson that I understood that the appellation was originally ironic rather than literal.

In 1948, Johnson had entered the primary election for the Senate against former Texas governor Coke Stevenson. Although Stevenson garnered more votes, he failed to reach a majority so a runoff election was held. Johnson was declared the victor by 87 votes—out of the 988,296 cast. That was the “landslide” that gave him his ironic nickname, not the actual landslide of 1964.

But wait there’s more.

Even that extremely narrow victory was based on 202 votes that turned up six days after the election from Box 13 in Jim Wells County. The 202 votes were coincidentally in the alphabetical order of registered voters, some of whom later declared that they had not voted. And apparently all 202 were cast using the same pen and in the same handwriting.

It was the final 87-vote margin that caused Johnson’s senate colleagues to tease him with “Landslide Lyndon.” Still, he rose quickly through their ranks until, in 1954, he became majority leader. I assume the teasing, at least to his face, had stopped by then. In 1960 John Kennedy, who had a funny New England accent, chose LBJ as his running mate to help secure the votes of Southern Democrats who spoke like normal Amerakunz.

With a resounding mandate in the ’64 election, LBJ implemented a very ambitious agenda he called the Great Society—civil rights legislation, Medicare and Medicaid, funding for education and the arts, and the War on Poverty. Unfortunately, he also greatly expanded American involvement in Vietnam from the 16,000 non-combat “advisors” sent by Kennedy to 525,000 actual combat troops in 1967. As casualties mounted, there were violent protests, civil unrest and riots in major cities—most notably at the Chicago convention of the Democrat Party. Anti-war senator Eugene McCarthy did very well in the New Hampshire Primary. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, LBJ announced that he would not seek re-election. His VP, Hubert Humphrey, went on to lose to Richard Nixon.

LBJ was a man of many contradictions who had a fascinating life and political career. But this is supposed to be a travel column. So, here you go.

As regular readers know, Shirley and I always deviate from the shortest route to our primary destinations with detours along the way. It takes us four or five weeks to get to our Arizona wintering grounds because there are pauses of a week or so in Gulf Islands National Seashore, Padre Island, Big Bend National Park, Saguaro NP, and other attractions. The trip home also meanders around quite a bit so we can visit places we have not been before or revisit old favorites.

Returning from Arizona this year, we left I-10 in the Hill Country of Texas to visit the Lyndon B. Johnson National Historic Park (the LBJ Ranch) and the LBJ State Park directly across the Pedernales River from it. The state park is worthy of a visit in its own right, but its name is rather misleading. If it were called the Sauer-Beckman Living History Farm, it would probably attract somewhat fewer visitors. An inducement to go there is that tickets for the LBJ National Historic Park are issued at the state park. Entry to both parks is free, by the way, but you are still supposed to get a ticket. After we got ours, nobody asked to see it.

Adjacent to the state park visitor center is a small museum that summarizes 10,000 years of history from the Paleo-Indians through the pioneer farming and ranching of the area. There are archeological and anthropological exhibits featuring Indian culture before the time Europeans showed up and ruined the neighborhood. Our friend Vicki insists that Indians should not be called that. They were misnamed, she says, because Columbus thought he had landed in India. So we should call them Native Americans. Perhaps she is right. Even so, it seems unlikely that they would call themselves Native Americans back when none of them spoke English and there was no such place as America. Even today, I’m betting that most Americans don’t know why we are called Americans. Except, perhaps, a few who are of Italian heritage.

Almost all aboriginal peoples everywhere in the world refer to themselves simply as The People in whatever language they happen to speak. The Apaches in Texas, for example, called themselves “N’de,” The People. Likewise the Comanche word “Nuhmuhnuh” means “The People.” The Tonkawa, in all modesty, called themselves Tonkaweya, “The Most Human People.”

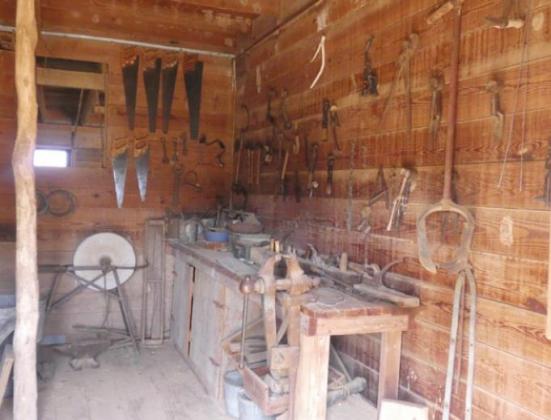

A short walk beyond the museum is the Sauer-Beckmann Living History Museum, a pioneer farmstead. (The area was settled by German immigrants as reflected in family names and Fredericksburg cuisine even today. It is easier to get a plate of sausages and sauerkraut than good ol’ Texas brisket.) The house built in 1869 by John Friedrich Sauer (who obviously was a Kraut) was originally a log cabin that grew in size with his family. Eventually he erected a two-story stone dormitory for the ten children.

In 1900, Sauer sold the house and 400 acres to Hermann Beckmann who sided over and painted the cabin to “modernize” it as an enticement for the girl he wanted to marry. There are barns, outbuildings, a garden with what are now heirloom vegetable varieties, some cows, pigs, and chickens. Volunteers in period costume explain and answer questions, in great detail, about the people who lived on the farm and their lifestyle.

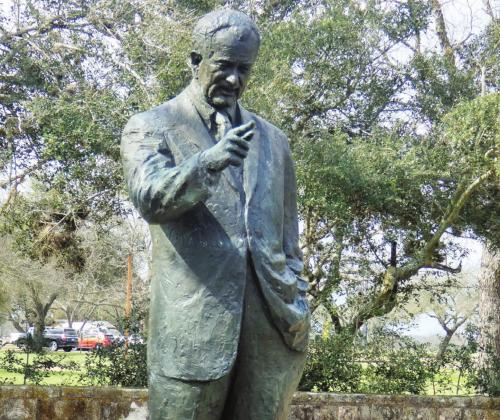

The park trail continues through a short stretch of woods to the pasture for longhorn steers and an enclosure for a small bison herd. The trail circles back around to the visitor center. Along the way is a statue of LBJ pointing towards the Pedernales as an indication of the critical role it played in his boyhood development and the love he felt for the area all of his life.

Taking a hint from the statue, we crossed the river to visit the LBJ National Historic Site, which, by the way, is still a working cattle ranch. First stop, directly across the bridge, is the one-room Junction School that LBJ attended beginning at age four. It is located conveniently next to his 1908 birthplace, which he rebuilt in 1964 as a guest house. And next to that is the simple farmhouse of his grandfather, Samuel Ealy Johnson.

Across the road is the Johnson Family Cemetery where President LBJ has an especially modest headstone that does not seem in keeping with his reputation for personal power and self-aggrandizement.

The road continues parallel with the Pedernales under a canopy of live oaks. White-faced cattle seek the shade of the trees and water of the river. They casually wander back and forth across and along the road, so we drove slowly. The road then loops through open pasture land where we saw more pronghorns and wild turkeys than cattle. That changed up at the Show Barn where ranch hands were busy and more cattle were lounging in the shade and scratching their backs on trees.

Down the center of the pasture runs an airstrip where LBJ’s jet landed on his frequent visits to the Texas White House. Air Force One, a jumbo 707, was too heavy for the airstrip so, at first, he flew into San Antonio or Austin and finished the trip by helicopter or car. Later, a smaller Jetstar allowed him to make direct flights from Washington. A hangar houses the Jetstar and a small LBJ museum. You can buy a Stetson just like the one Johnson wore for only $225.

From the hangar it is just a short walk to the original stone ranch house that, like the Sauer house, was greatly enlarged and modernized over the years. The original stone structure is still visible at the left end of the house. The ranch, when it was owned by LBJ’s uncle, Judge Clarence Martin, was where his boyhood summer vacations were spent riding and helping out with ranch work. In 1952, a more prosperous LBJ bought the property from his widowed aunt.

As with most national parks, we anticipated that there would be restricted access in late March because of COVID. In this case, however, COVID was not the culprit. The Texas White House is closed indefinitely while serious structural issues are being remedied. Though visitors cannot tour the inside, a self-guided walk around the property is still permitted.

Historic photos taken there during the presidential years show LBJ with foreign leaders, President Truman, Adelai Stevenson, his advisors and heads of departments, and Gen. Westmoreland with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara during the dark days of Vietnam. Earlier presidents had private retreats to get away from it all, but the LBJ Ranch became the first functioning White House away from Washington. LBJ didn’t get away. He brought it with him. Biographer Caro says that, as a graduate of Southwest Texas State Teachers College, LBJ sometimes felt a little intimidated around Ivy Leaguers and preferred to conduct business on his home turf.

Another part of that home turf is about 15 miles away at Johnson City, founded by his uncle James Polk Johnson on land bought from grandfather Samuel. There is the 1867 dog-trot cabin built by his grandfather when he operated a cattle-droving business. The dog-trot style is an iconic American log cabin with an open hallway or breezeway down the middle to improve air circulation and provide extra shade during Southern summers. There is an exhibit center that is said to tell the story of ranch life, cattle drives, and Texas pioneer life.

Uncle James’s house burned in 1918, but a barn remains as well as a windmill, water tank, and cooler house, which were important features of farming and ranching in those early days. As we approached, a groundhog went scurrying under the barn door. German immigrant John Bruckner bought property in the Settlement and built a cut-stone barn.

A few minutes’ walk from the Johnson Settlement is the LBJ Boyhood Home in Johnson City. He lived there from age five until he married Claudia “Lady Bird” Taylor. The house has been restored to its 1920s appearance, but it was closed because of COVID.

That was also the case with numerous other places we have been since early 2020. But the key message is that we were still able to visit numerous other places. Though many people were under house arrest for more than a year, RVers can easily social distance. Some of the restrictions we encountered made perfect sense. It was probably wise, for example, not to crowd 12 people into park vans for guided tours or 100 people into a theater to view the park film. Other restrictions were so ludicrous that even those who imposed them could not explain the logic. Some day we will look back and laugh. Some day. When more of us have broken our addiction to hand sanitizer and fanciful masks.

Still, there is little to be gained by whining about park closures and other restrictions during the worldwide COVID tragedy. If it turns out that those are the worst things that happen to us, I guess we can live with it. Millions did not. One result of Covid restrictions is that Shirley and I are even more grateful than ever for the thousands of times we have enjoyed a walk in the park. So, carpe diem, people. Tomorrow is promised to no one.

LeMoyne Mercer is the travel editor for Healthy Living News. There is limited space here for LeMoyne’s photos. You might want to see more at anotherwalkinthepark.blogspot.com. Please leave comments on the site.