ONE OF OUR FAVORITE SHORT TRIPS of a couple weeks or so is a loop through Great Smoky Mountains National Park, up the Blue Ridge Parkway to Shenandoah NP, and home via West Virginia and Maryland. Or vice versa. For either fall color or spring wildflowers, it is a simply stunning excursion.

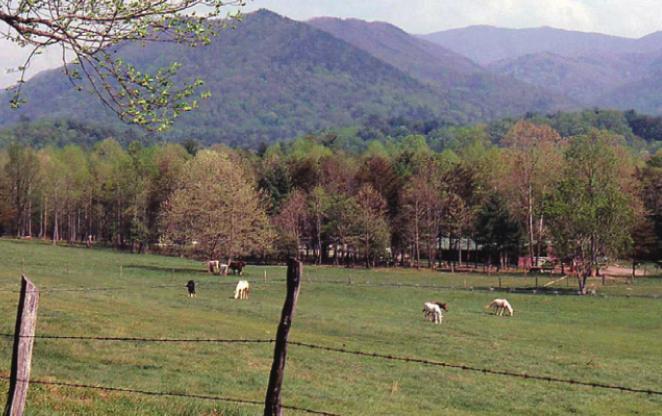

Cades Cove is in a corner of the Smokies reached via the twisty-turny narrow road that follows the Little River and Laurel Creek. Those tumbling mountain streams are just a few feet from the road on one side with a sheer rock wall on the other. Just getting there is an adventure— especially when on-coming traffic is nervous about hugging the wall. The Cove is a picturesque valley where open meadows are enclosed by misty mountains. The “smoke,” by the way, is caused by hydrocarbon molecules called terpenes given off by millions of trees. When they interact with sunlight, the molecules break down and reform as larger molecules that refract the sun’s rays.

The main attraction in the Cove is the one-lane, one-way, 11-mile Loop Road that takes visitors to historic farms, churches, and a grist mill. On Wednesdays, traffic is restricted to bicyclists and pedestrians. Skip breakfast and start the Loop when there is still a bright golden haze on the meadow and all the sounds of the earth are like music. You are almost certain to see numerous deer, flocks of wild turkeys, and, perhaps, a bear or two.

Unlike national parks in the West, land for the Smokies was purchased from private owners, not all of whom left willingly. They were descendants of pioneers who loved the place and had invested oceans of sweat equity. How do you put a price on that? There were once about 80 homes, four churches, and four schools in the Cove for a population of about 685. Most buildings were at the edge of the forest where the land begins to climb the mountains. The relatively level and rich, loamy soil of the valley floor was reserved for crops. Today, there remain six log cabins and a frame house, three churches, and the Cable Mill to show what life was once like in the Cove.

When we started taking family vacations there in the 1970s, there was still one functioning homestead where Kermit Cauhron had struck a deal with the Park Service. Cauhron, born in 1912, was a fifth-generation descendant of the original pioneer settlers John and Lurena Oliver. He was allowed to graze cattle and cut hay in order to keep the meadow from returning to the wild. We remember Cauhron as the old guy sitting in a rocker on his porch, soaking in the view and waving to passersby. Looking back, though, in 1975 the “old guy” would have been 63. Somehow, that no longer seems ancient. After he died in 1999, the house was demolished and the meadow is being reclaimed by wildflowers. Encroaching trees can’t be far behind.

But you never know. The Park Service could change its mind.

For example, in 2005, Shirley and I were walking along the Little River looking for a place to fish for colorful native brook trout. In a clearing, we came upon some derelict buildings. Roofs caved in and trees growing up through them. Walls and stone foundations collapsing. Heavy fluorescent orange plastic netting all around and signs advising not to enter because of numerous hazards. Including the resident rattlesnakes.

From 1910 until the establishment of the park, these were the vacation homes of people trying to escape the summer heat down in Knoxville. The park’s policy was to allow the cottages, like the Cove meadow, to return to a state of nature. Then they decided that the collapsing structures posed a hazard to park visitors and should be removed. Then they decided that, like the log cabins, those cottages were part of our cultural heritage and should be preserved. Some of them, anyway. So, they tore down and removed 34 and set about rebuilding four of them. In 2017 they were opened to visitors.

But how do we define our “cultural heritage”? At the Oconaluftee Visitor Center, I was admiring a display case of historic artifacts—Mason jars, a Coca-Cola bottle, other odds and ends left behind by the boys of the Civilian Conservation Corps who built the park. I asked a ranger how this stuff qualified. He responded rhetorically, “What’s the difference between garbage and a historic artifact? Fifty years.” Which is why half of what Shirley and I own is now national treasure.

But, back to the Cove.

The first stop on the Loop Road, not counting those for wildlife, is the John Oliver Cabin. He came in 1818 as a veteran of the War of 1812 and eventually became Kermit Cauhron‘s ancestor. The cabin is known for the quality of craftsmanship recognizable by folks who pay attention to the way logs interlock at corners. The cabin is also noteworthy because it was not actually John Oliver’s but the house he built for his son as a wedding gift. Like most of the original cabins, Oliver’s own no longer exits.

There is a short spur road a little farther along that takes you to the Primitive Baptist Church. Like much of Eastern Tennessee, the congregation remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War. Nearby are the Methodist Church and the Missionary Baptist Church. We can picture Sunday morning worshippers on foot and in farm wagons all headed toward the cluster of churches, greeting neighbors as they converged along the way.

There are interesting stories told by the grave markers in the church cemeteries. A marker identifies John and Lurena Oliver as the first settlers. William Hamby, Revolutionary War veteran. Russell Gregory, “Murdered by North Carolina Rebels.” As an OB/GYN nurse, Shirley was quick to note the number of infant deaths and those of their mothers. In the 20th century, we grew accustomed to most children outliving their parents and wives their husbands. Throughout all of history, though, childbirth was a significant risk for both mother and baby.

The Cove was, and still is, an isolated mountain valley. Visitors bringing news from the outside world helped create the reputation of residents for hospitality. Chief among these may have been Elijah Oliver, son of John and Lurena, born in their original cabin. Elijah moved away before the Civil War and returned in 1865 to build his own place. It is located somewhat off the Loop Road and requires about a one-mile roundtrip walk.

Part of the house sits over a cold-water spring that served as a “refrigerator” for eggs, butter, milk, and other perishables. In addition, his place included a chicken coop, corn crib, smokehouse, and barn because, in the 1800s, it was important to be as self-sufficient and independent as possible. Independent but still sociable. Which is why Elijah’s house included a room specifically set aside for guests—the Stranger’s Room— where travelers were welcome to a meal and a night’s lodging at no charge. Unless you counted several hours of conversation with Elijah as a price.

After Elijah’s place is a short spur road to the trailhead for Abrams Falls, one of our favorite hikes. It is about five miles round trip, mostly along Abrams Creek until it makes a short but steep climb over a ridge to reach the head of the falls. Like the Loop Road, it is best to go early in the day if you hope to enjoy a modicum of quiet. Solitude is almost certainly out of the question. By the time you start back, there will be an army of other hikers headed toward you. Still worth the effort, though.

At the far end of the Loop Road is the Cable Mill where the grinding of corn is demonstrated. Or was until COVID. We used to buy freshly ground corn meal there to make bread, muffins, and grits. There were once several grist mills and saw mills serving the Cove.

In 1879, Leason Gregg bought an adjoining acre from John Cable and built the first frame house in the Cove. Painted white, it looks surprisingly like a modern farm house. Until you look inside, of course. The Gregg family lived on the second floor and used the first floor as a store. In 1887, Gregg sold the place to Rebecca Cable and her brother Dan. After the death of Dan, Aunt Becky cared for his orphaned children and continued to live there until she died at age 96.

Another story: Matilda Shields Gregory and her young son were deserted by her husband, but her brothers and neighbors built her a replacement cabin that was small and rough because it had to be put up in a hurry. Later, Matilda married the widower Henry Whitehead who built her one of the finest cabins in the Cove. It is made of square-sawed logs that make it look almost like a frame house. And Henry made bricks for the chimney by hand instead of using stones. One might surmise that the exceptional effort that Henry made was an indication of…. Well, you decide what it probably meant.

The Tipton Place has a story we find fascinating for a different reason. Col. John Tipton and his son William (Fightin’ Billy) were veterans of the Revolution who settled in Eastern Tennessee. William later had a land grant of 640 acres in the Cove the way many veterans were paid for their service with land. Eventually, he owned a substantial portion of the valley floor.

The Tipton barn is a cantilever style that was common in Germany. Among the German emigrants was Casper Cable, a Hessian soldier in the employ of the British during the Revolution who was captured at the Battle of Trenton. (You probably remember that as the one when Washington crossed the Delaware and caught the British sleeping off their Christmas celebration.) Casper changed sides in exchange for his freedom. Like the Tiptons, he moved to Tennessee, and his sons Peter and Samuel settled in the Cove. They may have introduced the cantilever barn design. At minimum, they introduced the Cable name with which we are already familiar.

And here’s more about the Cables: Next stop is the Dan Lawson place on property bought from his father-in-law, Peter Cable, who was related to John of the grist mill. Peter was an expert carpenter and, therefore, assumed to have had a part in the construction of the cabin. The original part of the cabin is hand-sawed logs with a second floor of boards added when a water-powered sawmill came to the Cove. The property also has a barn, granary, and smokehouse. Smoking was a popular way of preserving meat, especially pork, before the days of refrigeration. We may have given up home butchering, but we still associate the great taste of bacon with hickory or apple wood smoke.

The Carter Shields place is close to the end of the Loop Road in a picturesque forest clearing. It is a hybrid structure that started as a log cabin but, like Dan Lawson’s place, later had a board addition. Though probably built by William Sparks, it takes its name from George Washington “Carter” Shields, son of Henry Harrison Shields and Martha Jane Oliver Shields, who was born in the Cove in 1844. At the beginning of the Civil War, Carter enlisted in the 6th Tennessee Volunteers—a Union regiment—and was severely wounded by artillery fire at the Battle of Shiloh. After his discharge, he lived in Missouri and Kansas before retiring to the Cove in 1910.

After our stay in the Cove, we take the Newfound Gap Rd. over the crest of the mountains to Oconaluftee right at the Cherokee, NC entrance to the park. Adjacent to the visitor center is the Mountain Farm Museum—a working farm with log farmhouse, barn, springhouse, gardens, and farm animals. Across the road is the Mingus Mill. Volunteers demonstrate how food was produced before the invention of Kroger. The farm sits at the southern terminus of the Blue Ridge Parkway that runs 469 miles north to Shenandoah National Park where the Parkway becomes Skyline Drive.

Last October, we met a woman who had driven part of the Parkway and was staying at a motel in Cherokee. She wanted to know if there was anything worth seeing in the Smokies. I mentioned a few.

“So,” she said, “just more of the same.”

“Yep, ‘fraid so.”

Still, Shirley and I think that the Smokies, the Parkway, and Shenandoah are a walk in the park—even if they are just more of the same.

LeMoyne Mercer is the travel editor for Healthy Living News. There is limited space here for LeMoyne’s photos. You might want to see more at anotherwalkinthepark.blogspot.com. Please leave comments on the site.