YOU CAN PROBABLY THINK OF A THOUSAND REASONS to go to Florida in winter. Especially if you spent this winter in Ohio. One of the things Shirley and I most look forward to in late February is the chance to attend the Winter Horse Trials at Rocking Horse Stables.

Central Florida is horse country. Drive any country road east or west of I-75, and you will find shoulder-to-shoulder horse farms. Before COVID, the Horse Trials attracted not only the locals but participants from all over North America, South America, and Europe. This year, participants came from the US, Canada, and Mexico to compete in the usual dressage, show jumping, and cross-country races.

Spectators are allowed to walk onto the cross-country course and choose a vantage point from which to enjoy the action. The only rule is to avoid getting run over by galloping horses. One of the judges told us she had to shout a warning to a man who was so engrossed in his phone that he wandered onto the course as a horse was galloping right at him.

The course is more or less challenging depending on the skill level of the horse and the rider. The Advanced class covers 3,460 meters with 23 jumps. Intermediates run 3,070 meters with 21 jumps. The Novice course is 2,420 meters and 18 jumps. But there is more than distance to distinguish the levels. The jumps are both higher and broader for the upper divisions.

The cross-country race starts one horse at a time with a two- or three-minute interval between contestants. They race against the clock rather than directly with each other. At the starting gate, the judge gives the rider a 60-second warning and counts down from 10 seconds as the horse enters the chute. At zero, the starter yells “Go!” and a few seconds later reports via radio that horse #54 left at 1:17 and cleared jump one. There is a judge at each subsequent jump to verify that #54 cleared the jump. Or not.

Shirley and I spend quite a bit of time at jump 22, the water hole, because it tends to be more dramatic. Horses emerge from a small copse of live oak trees that trail picturesque Spanish moss. They make a hard left turn and leap a barrier, landing in a shallow pond. Sometimes. Twice while we were there, the horse threw on the emergency brakes and declared, “I don’t think so!”

On one of those occasions, the rider circled back about 20 yards and made another go at it. In the other case, the horse adamantly refused and the rider told the judge he was resigning the race. The owner, standing next to us, said the horse was an “off-course thoroughbred” that required a little more training.

In the third incident, the results were potentially devastating. Horse and rider cleared the barrier without hesitation, splashed through 15 yards of water, leaped over another barrier resembling a four-foot-high red barn, made a sharp right, and scrambled up a muddy bank to clear another little red barn about five yards from where we stood. This time the horse, Jack, caught his rear hooves on the barn roof and took a tumble, landing with his rider trapped beneath him.

The jump judge was on the radio immediately. Within seconds, the EMTs and emergency veterinarians arrived. Several of them restrained the horse’s legs so he would not further injure his rider as he tried to regain his feet. They were able to roll him just enough to gingerly extract her from beneath him. She had remained motionless at first, and it appeared that she was unconscious, but, to our relief, she was soon able to move all extremities. The EMTs brought out a backboard and carefully moved her onto it and into an ambulance. Shortly thereafter, the vets got Jack on his feet. Though limping on his right foreleg, he appeared otherwise unharmed by the fall and was loaded onto a trailer.

A race official who had seen me photographing the incident came to ask that photos not be published as a courtesy to the rider and her family. (I didn’t have the nerve to tell him that, though HLN is popular, it is unlikely that her family would ever see the photos or story.)

Another rider told us that the Equestrian Federation is in the process of redesigning cross-country jumps to make them more forgiving. In show jumping, if a horse hits a rail, the rail falls down. In cross-country, if the horse hits the barrier, the horse falls down.

We are always impressed by the courage of both the horses and the riders that can approach an obstacle at full gallop without flinching. Consider also that, as in this case, the riders are often young women. They are not wimps. And the first thing this rider asked was if Jack was okay. So, I have a few broken bones and possible internal bleeding. No big deal. How’s my horse?

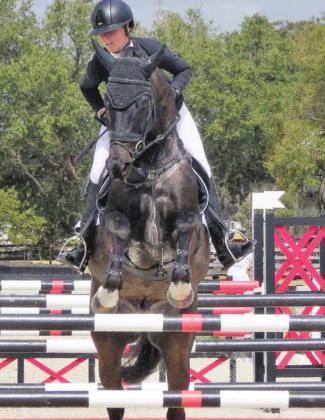

The show jumping events are also conducted in advanced, intermediate, and novice classes. These designations apply to both horse and rider. Sometimes a novice horse has an advanced rider to help with the training process. The higher the class, the higher and more numerous the jumps, sometimes in quick succession. It is always fascinating to watch the interaction between horse and rider. Some are rather matter-of-fact and businesslike. Sometimes there is a lot of vocal encouragement, patting on the neck, and atta boys.

Disasters in the show jumping ring tend to be a matter of embarrassment rather than threats to life and limb. The object is to clear all the jumps within the allotted time without knocking down any of the rails. Riders want to do well and look good doing it. It is a formal competition with specifications for appropriate attire and equipment. Because the competition is so photogenic, there are professional photographers who post their images online for purchase by riders and/or owners. I made a point of chatting up a couple of these pros because they knew where to stand to get the best angles. One of the horses crashed right into the jump. Didn’t knock off the top rail, just balked at the last second and knocked the whole thing down.

“Is he going to order a copy of that?” I asked.

“No,” she said, “Intermediates hate that. Novices would want it though.”

Sometimes the novice horses have their own personal quirks that need further attention. One horse did not exactly refuse the jumps, but he did hesitate just a beat, momentum lost, rhythm entirely broken, and sort of hop over. He cleared the jumps but looked mighty silly doing it. Well-trained horses with competent riders just go straight at the jumps, taking them in stride, making it look both easy and elegant.

Shirley and I went to a holiday performance of The Nutcracker. (Bear with me a moment.) The guest artist from the New York City Ballet was a gentleman of diminutive stature. He was paired with a woman of somewhat more robust proportions. Now, most ballerinas can help their partners make the lifts seem easy by their grace, fluidity, and timing. With perfect coordination, he can use her momentum to carry her upward, arms fully extended overhead, and gently deposit her in one uninterrupted motion.

Well, that’s not the way it happened. The little guy soon had wobbly knees, and you could almost hear him praying that he had remembered to bring his truss.

The horsey version of ballet is called dressage. Making specific equestrian movements look easy, fluid, elegant, and effortless is the point of dressage. It is the most technically challenging of equestrian events for both participants and spectators in part because they are supposed to make it seem effortless. There tend to be very few spectators, by the way, because it requires knowledge and understanding of quite subtle standards of performance in order to appreciate what is going on. In cross-country and show jumping, even the most obtuse of viewers can tell if the jump was cleared or not. In dressage, the judges and skilled participants are probably the only ones who can distinguish excellence from mediocrity.

Dressage is conducted in a 20 x 40 or 20 x 60 meter “ring.” (Obviously it is no more round than a boxing ring.) There are 12 or 17 letters along the edges, but they make no more sense than any of the other subtleties. Dressage is evidently of German heritage, so K=Kaiser, V=Vassal, S=Schzkanzler, F=Furst, etc. as the designations of where the required equestrian movements are to begin.

The object seems to be to avoid any signs of melodrama while making things look as controlled and boring as possible. No words of encouragement or rebuke from the rider. While the horse does his little pas de deux of specified formal movements, the rider’s job is to sit there pretending to do nothing. He puts the horse through his paces, literally, by barely shifting his balance in the saddle and with gentle pressure of the knees to help the horse perform appropriately. The horse demonstrates its skill, power, fluidity, and mastery of the required four-beat walk, three-beat canter, and two-beat trot. We have seen experienced riders guide a novice horse and an experienced horse train a novice rider.

Dressage training and discipline develops the natural athletic ability of both horse and rider. In cross-country and show jumping, there are no style points. In dressage, there ain’t nothing but style points. The team either performs the required ballet-like routine so gracefully that the judges are impressed or, occasionally, somebody’s knees sort of go wobbly. Shirley and I prefer cross-country and show jumping events because we lack the technical knowledge to appreciate the final points of dressage. As far as we are concerned, all the performances look pretty. And pretty much alike. Never notice any knees going wobbly. What we definitely can tell is that all the events in the Winter Horse Trials are just a walk in the park.

LeMoyne Mercer is the travel editor for Healthy Living News. If you are contemplating a trip, you might want to see photos and information about numerous destinations at AnotherWalkInThePark.blogspot.com.