SHIRLEY AND I SPENT JANUARY TO MID-MARCH IN FLORIDA, concluding our stay there with ten days at Gulf Islands National Seashore just off the coast from Pensacola. Then we continued to Cajun country in the Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana before heading home via the Natchez Trace Parkway that ends in Nashville.

Atchafalaya, just west of New Orleans, is the largest swamp in the US and home to the Cajuns, not to be confused with the Creoles. The distinction is actually quite simple. Or it used to be, anyway. The Creoles trace their heritage to the days when the French and Spanish traded control of Louisiana back and forth. Creole culture is a cosmopolitan blend of European and West African influences and is generally associated with New Orleans where many Creoles became prosperous and sophisticated urbanites. The history of Louisiana is a little

The history of Louisiana is a little complicated. (Isn’t all history?) The Spanish claimed the area for two hundred years but failed to sufficiently occupy it to keep intruders out. Louis XIV sought control of the Mississippi Valley all the way from New France in Canada to the Gulf of Mexico in order to block the British from expanding beyond the Atlantic coast. In 1698, Louis designated Pierre LeMoyne the Governor-General of the territory named for himself, Louis-iana. Pierre’s younger brother, Jean-Baptiste LeMoyne, was founder of New Orleans. (This is merely shameless name dropping—even though I have no connection with the LeMoynes.) In 1763, Louisiana was ceded back to Spain. Then, in 1800, it returned to the French through Napoleon’s conquests. But in 1803, Napoleon was running short of cash, so he sold Louisiana to Thomas Jefferson. The Louisiana Purchase covered a huge territory, all or part of what later became 11 states, much of it famously explored by Lewis and Clark. Who, by the way, started in St. Louis and headed northwest up the Missouri River, never entering what was later the State of Louisiana.

The Cajuns are descended from the Acadians, French Canadians evicted by the British from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in 1755 when the French lost those colonies after the Seven Years War—called the French and Indian War in America. (So much for blocking the British.) Cajuns were more rural than the Creoles, living by farming, fishing, and hunting. They continued to speak French that, over the years, evolved into a dialect somewhat different from the European version just as the Brits find American English incomprehensible. The Cajuns were proud of their culture and language, generally avoiding the kind of assimilation that characterized the Creoles.

Many of us know of Cajun culture via their cuisine, which is distinct and flavorful. On this and prior visits to Atchafalaya, Shirley and I have forced ourselves to consume crawfish etouffee, jambalaya, stuffed crab, catfish, shrimp, frog legs, gumbo, smothered chicken, pork stew, candied yams, pecan pie, and bread pudding. Oh, and something called bayou pasta of undetermined ingredients and ethnic origin.

The Louisiana marshland is prime rice-growing country, so the local foods, especially jambalaya and gumbo, are rice based. Jambalaya usually contains shrimp or crawfish, perhaps some chicken or game, andouille or boudin sausage, and the holy trinity (onions, celery, and bell peppers) spiced up with cayenne and paprika. Basically, they follow the old family recipe—take what you got and put it in. As a rural culture, this means extensive use of personally sourced fish and game.

Okra is the distinctive ingredient in gumbo, used as a thickener to enrich the textures. There are other thickeners, such as roux (flour and fat), but without okra gumbo just ain’t gumbo. Even so, there is no such thing as an “authentic” recipe for gumbo. It is essentially a New World version of bouillabaisse made, like jambalaya, from whatever is on hand and served as a thick soup on a bed of rice.

The spicy nature of Cajun cooking is exemplified by Tabasco Pepper Sauce, made at Avery Island. The “island” is actually a salt dome that extends far beneath the surface with a soil-covered top rising above the surrounding lowlands. You can tour the factory to see how the sauce is made and fermented in barrels. Visit the store where they have Tabasco flavored everything, including ice cream, and a dozen varieties of the sauce that are typically not available in stores. You can taste and purchase at the store or on the website. (Shirley advises treading very lightly with the especially potent Cayenne Garlic Sauce.)

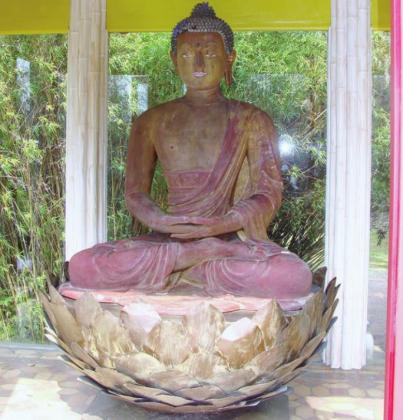

We think the real attraction, though, is the Jungle Gardens. Forget the cheesy name and take the three-mile drive, stopping often to get out and admire the floral displays, the great Buddha of Tabasco founder Edward A. McIlhenny, and his extensive egret rookery.

The 175 acres of gardens featureancient live oaks draped with Spanish moss. One of them, the 300-year-old Cleveland Oak, is named for the president who visited the McIlhenny family in 1891. There are also thousands of azaleas, one of the largest camellia collections in the country with 251 varieties, a long drive-through wisteria tunnel, an extensive display of English holly, as well as sago palms and 64 kinds of edible and timber bamboo.

Friends of McIlhenny discovered and purchased for him a 900-year-old statue of Buddha that had been left unclaimed in a New York warehouse. The Buddha was commissioned for a Shanfa Temple by Emperor Hui Tsung and stolen much later by a rebel warlord who shipped it to New York. To display this gift, McIlhenny designed and built an Oriental garden with an arched stone bridge and a Japanese red torii gate—a symbolic boundary marker for the grounds of the shrine. The focal point of this area is the large glass temple for the Buddha. It is still a place for ceremonies several times a year, especially on the birthday of the Buddha.

Another feature of Jungle Gardens is Bird City, the rookery McIlhenny built in 1895. At the time, egrets were being hunted for their plumage to adorn ladies’ hats. He helped save snowy egrets from extinction by capturing and raising eight chicks that were released when they were ready for the annual migration. The next spring, they returned with their mates as thousands of their descendants still do. McIlhenny protected the rookery from predators by constructing long, elevated nesting platforms above the water. The egrets have been joined by herons and other birds in great numbers.

Just a few miles north of Avery Island is a parallel experience at Jefferson Island. Joseph Jefferson was the son of theater parents who became a successful and wealthy actor in the late 1800s. This was almost exclusively the result of his adaptation for the stage of Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle, the story of a man who fell asleep for 20 years and awakened to find his wife dead, his children grown, and the world changed. Jefferson performed his adaptation more than 4,500 times on the stage and in an 1896 silent film. His success enabled him to purchase the property near New Iberia, Louisiana as one of his four opulent homes.

Like Avery, Jefferson Island is actually a salt dome, rising about 50 feet above the surrounding marshland. The aptly named Rip Van Winkle Gardens, like Jungle Gardens, has an Oriental flare with azaleas, camellias, bamboos, and statuary. Shirley and I had been looking forward to seeing the roseate spoonbills for which the Gardens are famous, but, in late March, they had not yet returned from their winter vacations in Mexico, Central and South America. So this time we had to settle for the four dozen constantly squawking peacocks. As at Avery, there is a 300-year-old Cleveland Oak with a bronze plaque saying the president took a nap under the tree. Of course he did. It is Rip Van Winkle Gardens after all.

Both of these estates are in Cajun country, but neither reflects traditional, rustic Cajun life. The Atchafalaya National Heritage Area was designated by Congress as a place of natural, historical, and cultural significance. (That definition is broad enough to include just about any area in the whole country they might later choose to designate.) The ANHA is not just the roadless swamp but the more habitable area just to the west reached by the 13-mile-long elevated portion of I-10.

On Bayou Vermilion is a historic Cajun community, Vermilionville, that eventually grew into the city of Lafayette, the Acadiana Capital of Louisiana. Today Vermilionville is a living history museum and folklife park. (Think of it as the Louisiana version of Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village.) There are representative Cajun homes, a trapper’s cabin, a blacksmith shop, a barn with animals, a school, and a church. Docents in period costumes explain and demonstrate what Cajun life was like in the 1800s.

After a marvelous meal at the restaurant (La Cuisine de Maman), we walked over to the Performance Center (La Salle de Danse) to enjoy the lively music of The Swamp Pop Express. There was a good deal of enthusiastic dancing by locals who seemed to know what they were doing. Or didn’t care what they were doing. Bobby Page, the 84-year-old founder of the band, wearing bright red shoes, joined in as lead vocalist on a few numbers. Did he still have the licks? Whatever he may have lost was made up for with sheer gusto. Based on the stomping and clapping, the audience was impressed that he was just able to stand up in the first place. A good time was had by all.

Now, Vermilionville is restored and recreated culture. Real Atchafalaya is still widely available in towns like St. Martinsville where St. Martin de Tours, the original 1765 home church of the Cajuns, is still an active parish. Behind the church is a statue of the heroine of Longfellow’s 1847 poem Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie about tragic lovers separated on their wedding day by the expulsion from Nova Scotia. Evangeline spent years in a fruitless search for her fiancé. In the nearby Evangeline Oak Park is yet another of those 300-year-old trees that has become a tourist attraction. It has an identifying placard even though Longfellow has nothing at all to say about such an oak. It’s not part of the story. Which is totally fitting. If Evangeline wasn’t real, why should her oak have to be real?

So, forget what I just said about the difference between actual and recreated culture. Things can get a little blurry when you’re talking about Cajuns. It is still likely, however, that Grover Cleveland took a nap under the Evangeline Oak after his walk in the park.

LeMoyne Mercer is the travel editor for Healthy Living News. If you are contemplating a trip, you might want to see photos and information about numerous destinations at AnotherWalkInThePark.blogspot.com.